SAC alumni membership

list

SAC Quad photos & names: 1947 | 1948

| 1949 | 1950

| 1951 | 1952

| 1953 | 1954

| 1955 | 1956

| 1957 | 1958

| 1959 | 1960

| 1961 | 1962

| 1963 |1964

| 1965 | 1966 | 1967 |1968

Great Chimney, Washington Column Direct Route. Photograph by Henry Kendall, 1958. Copyright ©2000 Estate of Henry Kendall. |

|

| SAC exhibit part 2 |

"I kept seeing rocks in my mind for days afterwards. I was just stunned and thrilled." --Meredith Ellis, climbing an overhang, Yosemite, 1962. Copyright ©2000 Wally Reed. Meredith Ellis Collection. |

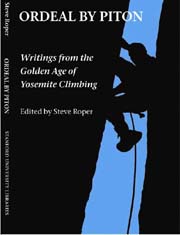

The Stanford Alpine Club was one of America's prominent college climbing clubs. Its identity was forged in the crucible of Yosemite Valley's smooth, steep granite. Members made important contributions to the development of modern Yosemite rockclimbing technique and helped carry the lessons learned to the world's great ranges. Coeducational membership was another factor distinguishing the SAC from the longer-established and better-known eastern clubs, and a tradition of "manless climbing" dated from the club's 1946 inaugural year. In the foreword to The Stanford Alpine Club, climbing historian Steve Roper writes "Nothing lasts forever, and for various reasons, the Stanford Alpine Club no longer exists. But nostalgia persists, and the story of this remarkable organization begged to be told. [It] is a testament to an era when young, enthusiastic college kids simply went out and had good fun in the mountains. Look at these rare, often exquisite, photos. Ponder the Pleistocene equipment and clothing we old-timers once were so proud of. . . . You'll be transported back to an innocent time."

|

|

When Stanford Alpine Club members occasionally paused from conversations of recent accomplishments and future plans and reflected on Stanford's mountaineering heritage, they contemplated a noble tradition stretching back through a web of connections involving Sierra Club climbers and its Rock Climbing Section, the legendary alumnus Walter Starr Jr., '24, Professor Bolton Coit Brown and his wife Lucy Fletcher Brown--all the way to the beginning of the university in the person of its first president, David Starr Jordan.

left: Freddy Hubbard demonstrates how to avoid curfew restrictions by rappelling from a Roble Hall window, 1947. Winifred Brown Collection. The new club drew some of its membership from the student hiking club that Cynthia Cummings, Freddy Hubbard, and three other Colorado friends had formed in 1945. Climbing, however, was what the coeds desired.

|

|

At Stanford the existence of the Alpine Club is as precarious as it is precious: The club exists in terms of a nucleus of avid climbers, sentimental enough to want to express their esprit in objective, institutional form, and proud enough to desire independence of the Sierra Club. But the Alpine Club has not always existed at Stanford; it was founded and has flourished in peculiar times, and how long the club can survive will always be problematic. --Dave Harrah, 1951 Through the summer of 1946, Larry Taylor worked on plans to form a climbing club at Stanford when he returned for graduate work in civil engineering. Then in August he chanced upon Al Baxter buying hobnails in the campus shoe shop, giving himself away as a mountain climber. "Though he had never done any roped climbing," wrote Taylor, "Al was at once enthusiastic about my plan; indeed it was his enthusiasm which had a great deal to do with the actual carrying out of the idea." The third founding member, Fritz Lippmann, the only experienced climber of the group, Taylor had met during Sierra Club Rock Climbing Section outings.

|

below left: Some of the members of the Stanford Alpine Club in its first year.

Stanford Quad, 1947. |

|

The personal connections and corporate traditions that bound one class to another became the SAC's strength. One such connection was between founder Fritz Lippmann and Dave Harrah, and then between Harrah and members who would become club leaders into the 1950s, including Jon Lindbergh and Nick Clinch. Lindbergh, Clinch, Dwight Crowder, Sherman Lehman, and Rowland Tabor were examples of the club's ability to attract, train, and retain a nucleus of leaders that would guide it through the fifties in the form established by the founders, strengthened by Harrah, and carried on by a cadre of new club presidents with a shared vision and commitment to the club.

right: Dave Harrah preparing to rappel from the roof of Encina Hall in 1948. Copyright ©2000 Dave Harrah. |

|

Approaching Hidden Peak. Copyright ©2000 by Bob Swift. In his book A Walk in the Sky, Nick Clinch told how while sitting twenty-eight days in a storm-bound tent in the mountains of British Columbia, clutching tent poles to prevent them from breaking, morosely contemplating the lowering white veil of the first of several blizzards that would plague the forty-day duration of the 1954 Stanford Coast Range Expedition, he formed the conviction that he and his fellow SAC climbers could actually succeed on an 8,000-meter peak. "Surely the Himalaya could not be worse than this," Clinch mused. "Why not go there?" "That was my great insight," he reflected. "And I was proved right." Clinch and his comrades would be the only Americans to do a first ascent of an 8,000-meter peak. Fanshawe and Venables wrote about Hidden Peak in Himalaya Alpine-Style: Nick Clinch led the successful 1958 American Expedition. His team, with the exception of Pete Schoening who had climbed on K2, was made up of old friends with relatively little altitude experience. . . . Clinch himself did not reach the summit of Hidden Peak but masterminded the first ascent, two years later, of Masherbrum and was a member of that expedition's second successful summit party. His contribution to American mountaineering is thus profound, though he was never to gain the same acclaim as his countrymen who were to climb Everest and K2 in the following decades.

|

|

Women climbers distinguished themselves beginning in the club's first year when Mary Sherrill and Freddy Hubbard became the third and fourth women to climb to the top of Higher Cathedral Spire in Yosemite Valley. Later Hubbard made the first ascent by a woman of the Washington Column Direct Route. The club's tradition of "manless" climbing dated from 1947. In 1952 Jane Noble, Mary Kay Pottinger, Gail Fleming, and Bea Vogel made ascents of Mt. Moran, the North Ridge of Middle Teton, and the Southwest Ridge of Symmetry Spire. In 1965 Irene Beardsley and Sue Swedlund made the first all-woman climb of the awesome North Face of the Grand Teton, the most famous north face in the United States. Climbing historian Chris Jones called that adventure "probably the most arduous all-woman ascent then made in North America," and Beardsley "one of America's best women climbers." Freddy Hubbard and her Roble Hall companions were not merely beneficiaries of the new club's coed-friendly attitude. Experienced mountaineers all, they were important contributors to the SAC's success. right: Su Wheatland belays Bea Vogel on the Monolith, Pinnacles National Monument, 1952. Copyright ©2000 by Richard Irvin. |

|

| John Harlin atop the Aiguille du Fou after the first ascent of its south face, 1963. Copyright ©2000 by Tom Frost. |

Throughout the 1957/58 school year Mike Roberts, Lennie Lamb, Henry Kendall, Dave Sowles, and Gil Roberts were working on their contributions to a new edition of the Stanford Alpine Club Journal. Gil Roberts, back from his summer first ascent of Mt. Logan's East Ridge, was also planning to join Nick Clinch's 1958 American Karakoram Expedition to Gasherbrum I.

In addition to the challenge of the

great Himalayan peaks, a second test of American mountaineering

beckoned. The most severe routes of the Alps, including the Walker Spur

of the Grandes Jorasses and the Eigerwand, awaited American ascents, as

did major lines and faces yet unclimbed. Club members were learning

skills and forging relationships that would help them accomplish these

mountaineering goals.

John Harlin and Gary Hemming would lead the way in a breakthrough for

Americans climbing in the European Alps. Kendall joined Hemming on the

Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses, the first American ascent of that

classic climb, "a route to dream of, perhaps the finest in existence."

Frost joined them on some of their greatest first ascents: the South

Face of the Fou and the Hidden Pillar of Fréney. These adventures on

great mountains had their beginnings in small places, on Sunday outings

to Miraloma Rock and Hunter's Hill, with the Stanford Alpine Club.

Tom Frost grew up in southern california and became a national champion in sailing as a teenager. At Stanford he majored in engineering, rowed crew, and kept on looking for what he called "the real thing." He found it after meeting SAC members and seeing Henry Kendall's photographs. He joined the club in 1957, rising quickly to the front rank of American climbers. In 1960 he was invited to join the team attempting the first continuous ascent of El Capitan. Frost knew nothing of photography but recognized the visual potential. Bill "Dolt" Feuerer had been on that wall and offered his camera to Frost, along with instructions on how to use it. The historic ascent took seven days, and Frost's innate visual talent was revealed on six rolls of Plus-X film. On his El Cap ascents in the 1960s Frost used a Leica IIC 35-mm camera with a collapsible 50-mm 3.5 Elmar lens. In less daunting places he used a 4x5 view camera and tripod, for which he built a carrying case that attached to a Kelty pack frame. But climbing still came before photography, Frost said; and on his major ascents, where survival itself was often in question, he carried the smaller instrument. In Big Walls: Breakthroughs on the Free-Climbing Frontier (Sierra Club Books, 1997), Paul Piana wrote that Frost "more than any other climber conveyed what it felt like to dangle thousands of feet off the ground. Tom Frost's beautiful black-and-white photos are still among the finest and most inspirational examples of climbing photography." Glen Denny said of Frost: "Most of the climbing photos you see now are prearranged setups for the camera on much-traveled routes. The impressive thing about Frost is that his classic images were seen, and photographed, during major first ascents. In those awesome situations he led, cleaned, hauled, day after day and--somehow--used his camera with the acuity of a Cartier-Bresson strolling about a piazza. Extremes of heat and cold, storm and high altitude, fear and exhaustion . . . it didn't matter. He didn't seem to feel the pressure." |

| SAC exhibit part 2 |